- © 2003 - 2025 Dynamix Productions, Inc. Contact Us 0

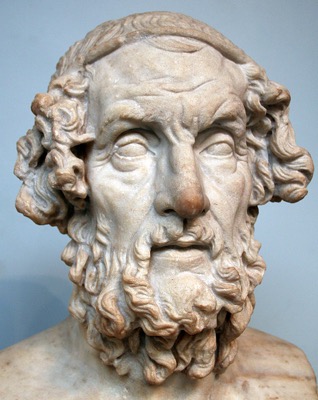

“There is a time for many words, and there is also a time for sleep.”

Homer, The Odyssey

If you've read The Odyssey or The Iliad, then you know why they've been literary classics for almost 3,000 years. But did you know they date to the earliest origins of the alphabet? It's believed that Homer's poems and speeches were so revered that early scribes dedicated themselves to writing them down. In fact, half of all Greek papyrus discoveries contain Homer's works. Homer must have been one cool dude to influence all of Western literature.

Now put on your time-travel caps and flash forward to the 1933. It's the early years of recording audio. Huddie Ledbetter was incarcerated in a prison in Louisiana when a father and son recording team came by. John and Alan Lomax were traveling the south on the dime of the Library of Congress to record and document African-American folk and blues musicians. John had found the LOC collections woefully inadequate and got funding to buy a "portable" (315 lbs.) disc recorder. There in the Angola Prison was the singer and 12-string guitar player better known as "Led Belly." Their collaboration over the next several years cemented Led Belly's place as a folk and blues legend.

Humans have long been documenting events with paintings on cave walls; sculptures; writing on papyrus; photographs; records and tapes; and film and video. One way we're doing it today is with oral histories. "Oral history" is a term used to describe recording someone relating personal experiences on audio or video. It's often used to supplement documents, pictures, artifacts, and visuals about an event or time period. Scholars say oral histories are a unique part of understanding history. Just hearing speech inflections and emotion in one's voice speaks volumes that printed text cannot.

Searching for key words in printed or digitized text is easy. Searching recordings can be extremely time consuming. In the past, recordings were done on disc or tape, so one had to listen to the whole recording. If they were lucky, a transcript existed. Recordings were usually only transcribed If funds, personnel, and time were available. But most recordings are in boxes collecting dust.

These days, oral histories are recorded digitally, an obvious quality advantage over analog. But the not-so-obvious advantage is search-ability. Doug Boyd of the Louis B. Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky has developed a novel searchable method called OHMS (Oral History Metadata Synchronizer). Any content in the Nunn Center's online files can be searched using current speech recognition algorithms. It's not perfect, as Boyd points out, but it's a step in the right direction.

Anybody that's used Siri or Google voice search will understand that speech recognition is not perfect. OCR (Optical Character Recognition) was at this stage about a decade ago. Now, document scanners can scan, ingest, and convert paper text to a digital file in seconds with few errors. But the complexity of speech patterns, accents, and recording quality will demand more intricate software solutions. This will come, and oral history repositories will reap the benefits.

All this bleeding-edge technology like the alphabet and records lead me to wonder what the next thing is? Thought recording? Memory mining? Oh boy, now everyone will know I really wasn't that cool in high school. I was really a nerd. Oh wait, you already figured that out.