- © 2003 - 2025 Dynamix Productions, Inc. Contact Us 0

Captain of the 'Weser': What's it like down there, in a submarine?

Der Leitende: It's... quiet.”

Das Boot, 1981

Submarines need to be stealthy...and quiet. New technology like acoustic cloaking is on the horizon.

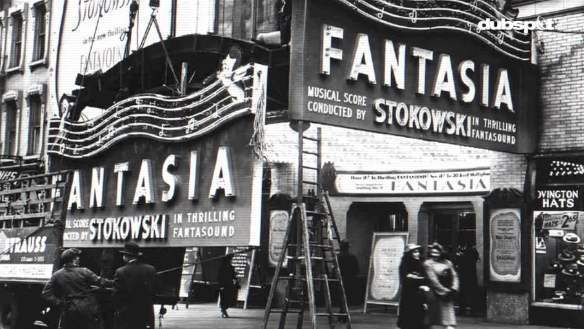

Mickey Mouse: Mr. Stokowski. Mr. Stokowski! Ha! My congratulations, sir.

Leopold Stokowski: Congratulations to you, Mickey.

Mickey Mouse: Gee, thanks. Well, so long. I'll be seein' ya!

Leopold Stokowski: Goodbye.

In 1940, before the world would be plunged into a half decade of devastating conflict, a larger-than-life cartoon creator teamed up with a wild-haired orchestra conductor and unleashed a fantastical film that would forever change the way we experience movies. The morning after the gala event at the Broadway Theater in New York City, The New York Times critic Bosley Crowther said, "The music comes not simply from the screen, but from everywhere; it is as if a hearer were in the midst of the music." Even with all the wondrous characters, vivid animation, and whimsical storytelling of this new film, it was the sound that stole the show.

"All you need is love. But a little chocolate now and then doesn't hurt."

Charles M. Schulz

Chocolate MilkThere's a phrase we use in the audio industry to explain to someone that doesn't understand that when something's been mixed down, like a song, it can't be unmixed. In other words, once all the elements have been married together, we can't easily pluck out the vocals and replace them. The phrase goes something like, "Here's a glass of milk, and here's chocolate powder. Mix the chocolate into the milk and you have chocolate milk. You can't take the chocolate out and just have milk."

Well, we are all eating a big ol' crow sandwich with chocolate sprinkles on top right about now.

"Well-timed silence hath more eloquence than speech."

Martin Farquhar Tupper

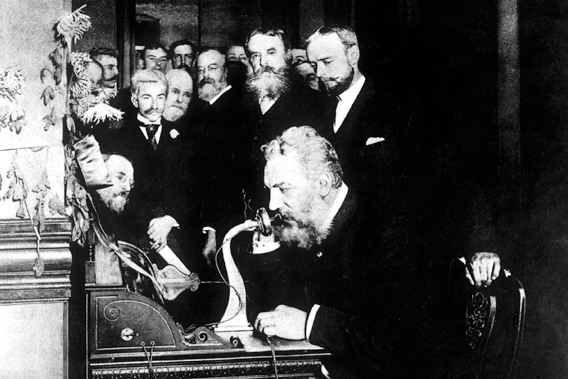

For the first century of our nation's existence, a very select few ever heard their president speak. 130 years ago, technology changed that.

"I think reincarnation is possible. Hopefully, we all get recycled."

Christina Ricci

We all should recycle. A look at repurposing old audio gear into funky new uses. Plus find out the latest news from Dynamix Productions.

- Lt. Werner: What's going on? Why are we diving?

- 2nd Lieutenant: Hydrophone check. At sea, even in a storm you can hear more down here than you can see up there.”

Das Boot

In the near future, submarines might be using sound waves to communicate through ocean waves. Intriguing, but let's first look at the history of how submarines communicate, problems they face, and why this emerging technology may be the new wave of submerged communications.

"I got a chain letter by fax. It's very simple. You just fax a dollar bill to everybody on the list."

Steven Wright

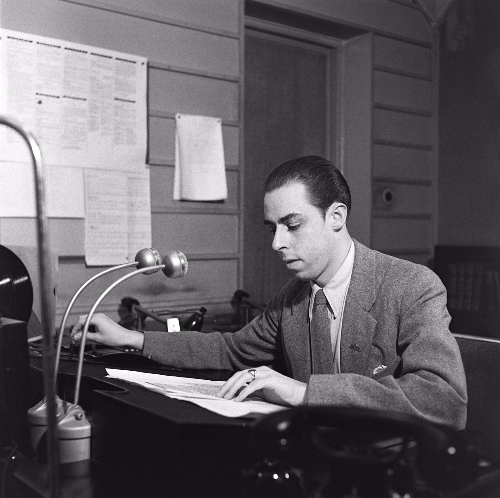

William G.H. Finch had a crazy idea. He liked efficiency, and he liked news. He imagined a future that would merge those together for the average American. Americans like Joe and Jane. When they woke up in the morning, this crazy idea goes, a box in their parlor had just printed out the latest news onto paper with stories and pictures, ready to be poured over while eating their breakfast. Wait – that kinda sounds like the here and now. What's crazy is that this brainchild was born in 1933.

"Well, folks, now we've got free baseball!"

Baseball announcer Skip Caray whenever a game went into extra innings

We're so used to living in a litigious society that when someone says "free," But now there are two exciting web sites for music lovers to explore that are...wait for it...free!

Read More...

"In radio, you have two tools. Sound and silence."

Ira Glass

As the world holes up in their houses during this coronavirus, as we absorb media like never before, as we listen to the news coming out of our television and radio speakers, we see and hear just how serious most of us are taking this. Journalists are broadcasting from their backyards, their sources are interviewed over Skype or Zoom, and the news now looks and sounds less-than-polished. It's like Sunday afternoons on FaceTime with the family three states away. These are the choices we are having to make these days: quality of content over quality of sound and video. But we don't know how good we got it.

"These fellows blow their horns just to see the people jump, I believe."

Chicago Mayor Carter Harrison, 1902

At the turn of last century, the automobile was poised to overtake the horse as the preferred mode of personal transportation. But there were detractors to the coming sea change. Much as we see driverless cars as a potential danger today, "horseless carriage" opponents saw the drivers themselves as dangerous.

Read More...

"All that's to come

and everything under

the sun is in tune

but the sun

is eclipsed by the moon."

Roger Waters

from "Eclipse" on the 1973 LP release "Dark Side of the Moon"

For generations, humans have been trying to link sound and light together. We have succeeded.

"Again and again, the cicada's untiring cry pierced the sultry summer air like a needle at work on thick cotton cloth."

Yukio Mishima

Recording location audio outside can be challenging at best. The video team wants an exterior shot because architecture or a landscape in the background can add to the image. But alas, there are often unwanted sounds like cars, HVAC blowers, and other manmade annoyances that we must work around. There's one sound though that is nearly impossible to eliminate, fix, mask, hide, or yell-at-to-be-quiet. It is guaranteed to ruin almost any exterior recording in the summer: the mating song of the cicada.

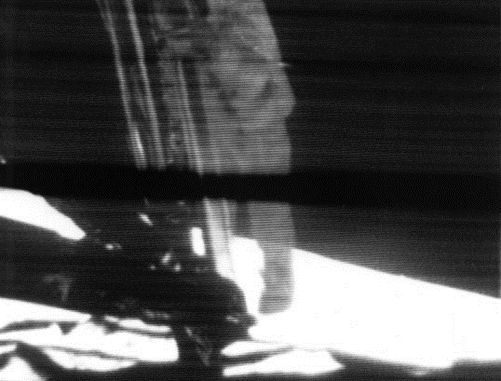

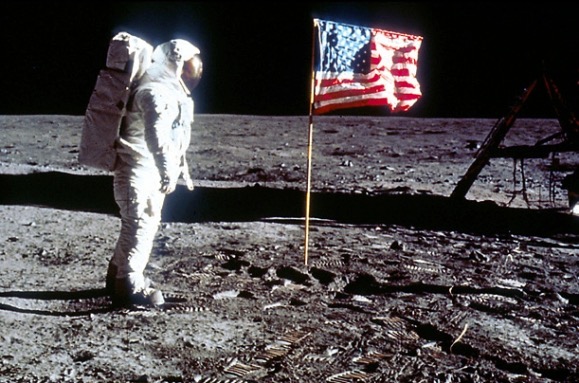

"It's an interesting place to be. I recommend it."

Astronaut Neil Armstrong commenting about the moon

Every time I hear the timeless phrase Neil Armstrong uttered while stepping on the moon, I can't help but remember the first time I heard it. It was 50 years ago at about 11:00 PM on July 20, 1969. I was eight-years-old and had fallen asleep waiting for them to get out of their strange looking space craft. So, rubbing my sleep filled eyes, I watched a white Gumby-like figure bounce down a ladder and onto the surface of another world. Then Armstrong delivered what is probably the shortest, yet most famous speech in all of human history, "That's one small step for man...." We strained not only to see him, but to hear him. "One giant leap for," he continued, "m_-_//_ _nd." What? There was static at the end covering the last word. What did he say?

"Radio is a hungry monster that eats very fast."

Tyler Joseph

Everything today seems to be sped up. We speed to work, we speed to pick up the kids, we speed home, we speed around the kitchen, we speed watch TV, we speed listen to podcasts, we speed, speed, speed...then we speed sleep so we can get up and do it all over again. And as if on cue, much of what we watch and listen to is also sped up.

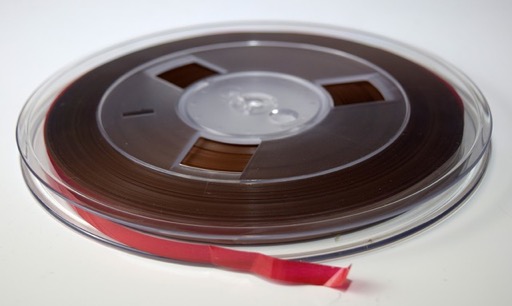

"It was easier just to say it out on a tape than trying to write it because it will take a lot of writing paper in order to get it straight."

Private First Class Frank A. Kowalczyk

Long Binh Post, Vietnam, 1969

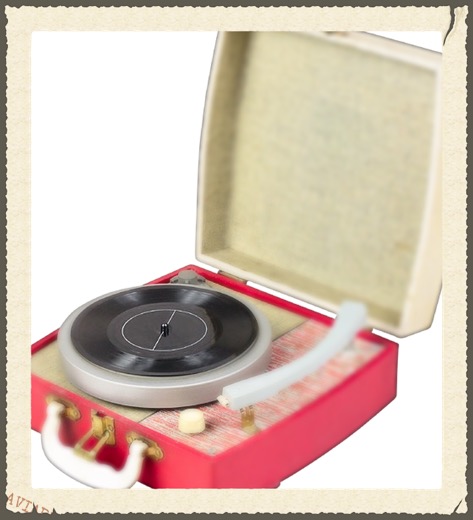

Back when it was expensive, or impossible, to call someone long distance, friends and family members would send messages on records and tapes to each other through the mail. Not only was it more affordable, it was a more personal way to stay in touch with each other and have some fun doing it. When I digitize some of these audio letters for customers, and feel like I'm transported back in time that a way that a letter can't take me.

"Nostalgia is not what it used to be."

Simone Signoret

Record stores all over America will be opening their doors on April 13th for National Record Store Day. But cassettes are sneaking in through the back. These portable petite plastic packs from the past now have their own Cassette Store Day each year in October, and they're winning over some fans that also shop for vinyl. In fact, annual sales of music cassettes were up 23% in 2018, and 70% since 2016. Artists and studios are rethinking this ancient format and not only re-releasing albums popular during cassette's halcyon days, but new music as well. What's with the retro rewind?

"TV gives everyone an image, but radio gives birth to a million images in a million brains."

Peggy Nooman

The recent presidential elections in Nigeria and Senegal stirred fond memories of my childhood. Specifically the "sounds" of Africa I remember growing up with. I haven't had the good fortune to go to Africa, but I've listened to it from afar. In the 1960s and 70s, radio was perhaps at its peak. AM radio stations played the hits, FM radio played the albums, and CB radios were in kitchens and cars. A lot of homes also had a shortwave radio. Today it's the internet that ties us all together. Back then, CBs connected us with our friends, AM and FM connected us with the country, and shortwave connected us with the world.

10:40 p.m. “I got about 2,000 college students coming from Walnut Street to 30th to Center City.”

10:46 p.m. “It’s endless, chief. Endless.”

11:11 p.m. “They’re on top of trash trucks. There is to be no one on top of trash trucks, guys.”

11:14 p.m. “We have multiple people on Broad Street swinging on light poles.”

11:20 p.m. “Climbing the trash trucks at 13th and Market.”

11:25 p.m. “I need to get the fire extinguisher out of my trunk. I got a fire on Broad Street just south of South. Someone lit a Christmas tree on fire.”

Philadelphia Police radio transcripts after the Eagles won the 2018 Super Bowl

Do you remember the old movies from the 1930s when a radio in a police car would blare out "Calling all cars! Calling all cars!" The diligent policemen would zoom away in their car with the siren screaming. The dispatcher had no idea if the radio cars heard the frantic call because two-way radios were uncommon and expensive. So from the late 1920s until after World War II, most police departments relied on their cruisers having radio receivers only. Today, police use digital radio systems that carry data, video, and other information.

"Hostilities will cease along the whole front from 11 November at 11 o'clock."

Marshal Foch, the French commander of the Allied forces via radio atop the Eiffel Tower.

This week marks 100 years since the end of the war to end all wars, known today as World War One. In 1918, on the 11th hour, on the 11th day of the 11th month, 1,500 days of fighting came to an end. The armistice was agreed upon just six hours earlier in a railway car halfway between Paris and the Western Front. What's remarkable is the speed at which most troops were informed of the impending armistice. This war, like in so many other ways, forever changed the world of communication.

"Hello from the children of Planet Earth"

From the gold records aboard the twin Voyager spacecraft

Vinyl is the format that won't die. It'll probably still be around after humans are extinct and our sun has gone supernova. Perhaps in eons, Voyager spacecraft with the golden records aboard will meet distant stars and future vinyl lovers. But in this eon, people will not stop pushing vinyl to its limits. Mad scientists and crazy artists like putting something other than music on it - or in it. More on that later.

Read More...

"He who knows that enough is enough will always have enough."

Lao Tzu

Father of Taoism

When is enough, enough? When do you stop finessing, polishing, correcting, perfecting, or otherwise fixing something important you're working on? When you're done – either because of deadline, budget, or exhaustion – are you satisfied? Something I like to say about my favorite projects is that I'm never really done with them, I just ran out of time

"My roommate got a pet elephant. Then it got lost. It's in the apartment somewhere."

Steven Wright

It started with insects. Caitlin O'Connell-Rodwell, PhD, an ecologist at Standford University, was working on her master's degree in entomology. Part of her research included recording love songs of Hawaiian planthoppers. They were communicating seismically (with really, really low sounds) through their limbs. Later, O'Connell-Rodwell was observing elephants in Namibia when she noticed the herd freezing, flattening their ears, and raising up on their toes. After field tests, she concluded that elephants can listen through their limbs and recognize warnings from particular elephants or herds miles away. Sensing low vibrations in the ground, elephants have been known to travel hundreds of miles toward storms for water, and flee threatening helicopters a hundred miles away.

“My dear girl, there are some things that just aren't done, such as drinking Dom Perignon '53 above the temperature of 38 degrees Fahrenheit. That's just as bad as listening to the Beatles without earmuffs!”

James Bond

"Goldfinger" (United Artists)

The other day, someone said to me, "You must have golden ears." He was referring to my profession as an audio engineer. He assumed that I physically had much better hearing than the average person. I don't. In fact, I often have trouble hearing conversations at loud parties and can't hear high-pitched whines that drive 20-somethings crazy. But I do think I have better hearing than a lot of other middle-aged folks only because I've protected it all these years.

“The only real way to disarm your enemy is to listen to them.”

Amaryllis Fox

Writer, peace activist, former CIA Clandestine Service officer

Eavesdropping on the enemy in times of war can be essential to victory. During World War Two, a tucked away family farm in New England would save thousands of lives while being a key to Allied victories over Germany and Japan.

"The people will waken and listen to hear

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere."

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

What did Paul Revere's famous midnight ride from Boston to Lexington sound like in April 1775? If you were there, you might recognize the approaching horse as a Narragansett Pacer mare. This once popular breed of horse, now extinct, was known for its ambling gait: a smooth riding four-beat gait that is faster than a walk, but slower than a canter or gallop. You might also notice the calm surroundings interrupted occasionally by crow calls, trees rustling in the wind, or the occasional farm dog barking at the stranger barreling down the rough dirt road. Just someone in a hurry.

"I have been at work for some time building an apparatus to see if it is possible for personalities which have left this earth to communicate with us."

Thomas Edison, 1920

What if you nonchalantly recorded something around your house, let's say a music practice session. Then when you played it back, you clearly hear someone whispering. You didn't hear it when you recorded it, so what was it? Many unfamiliar sounds throughout history can be attributed to nature, machinery, and even hoaxes. As our post-industrial society grows, so does the list of unexplained sounds, like trumpet sounds from the sky, humming cities, and ocean whistles. The proliferation of audio and video technology has generated its own tally of the strange. Specifically, weird voices that have been inadvertently and unknowingly captured. These recordings and transmissions sound eerie but have a very unsexy-sounding name: "Electronic Voice Phenomenon," or EVP.

"Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic."

Arthur C. Clarke

To the average person, audio can be a mysterious "myth-terious" thing. Many people don't want to admit that they are intimidated by the technical side of it, and that makes sense. The closest most people get to manipulating audio is adjusting the volume on their stereo. I bust 10 common myths about recording audio.

Shadow: No, Mary. I suspected a trap, so after I opened the door, I walked across the room and stood behind them.

Apple Mary: But your voice.... it came from near the door.

Shadow: Ventriloquism. A simple trick of projecting the voice.

The Shadow

"The Blind Beggar Dies"

Radio broadcast: April 17, 1938

We're fooled by Mother Nature all the time. She uses light to conjure up a mirage on a hot desert day and Aurora Borealis on a cold Alaskan night. She also has a bag of tricks for sound, like flinging noises a hundred miles away. But one of her best is when she makes sound disappear. This slight-of-hand by Mother Nature may have even changed the outcome of several battles in the American Civil War. What are these shenanigans of sound? Magic? Illusions? Sorcery? As the old radio serial hero said, "Only The Shadow knows." They're called acoustic shadows.

"At one time there were voiceover artists, now there are celebrity voiceover artists. It's unfortunate because these people need the money less than the voiceover artist."

David Duchovny

What does it take to perform a voice-over? After talking with several industry veterans, it turns out that it's not as easy as they make it sound - and that's the whole point. In Part 1, we found out how these four voice-over artists got into the profession. In Part 2, we learned about preparation and technique. In this last installment of our series, our nimble-tongued pros have advice to budding narrators and writers.

"In voice-over work, you have to actually do more work with your facial muscles and your mouth. You have to kind of exaggerate your pronunciation a little bit more, whereas with live action, you can get away with mumbling sometimes."

Mark Valley

What does it take to perform a voice-over? After talking with several industry veterans, it turns out that it's not as easy as they make it sound - and that's the whole point. In Part 1, we found out how these four voice-over artists got into the profession. This month, we learn the nitty gritty of preparation and technique.

"One of the things that I love about voiceover is that it's a situation where - because you're not encumbered by being seen - it's liberating. You're able to make broad choices that you would never make if you were on camera."

Mark Hamill

What does it take to perform a voice-over? After talking with several industry veterans, it turns out that it's not as easy as they make it sound - and that's the whole point. We find out that each of these voice professionals have their own approach to achieving the nearly impossible task of a voice-over artist: making it sound sincere. Plus, find out what's been happening at Dynamix lately.

"The opera ain’t over until the fat lady sings."

Ralph Carpenter, Texas Tech Sports Information Director

Richard Wagner, the 19th century German composer, would have loved Star Wars. He may not have understood what a light saber or X-Wing fighter was, but he would get it - even with his eyes shut. That's because the Star Wars films are rich with composer John Williams' scores that employ a musical tool that Wagner himself was a master of: the leitmotif.

"I like to be surrounded by splendid things."

Freddie Mercury

Ever since recordings progressed from mono to stereo, audio producers have been trying to create the ultimate immersive sound experience. You won't believe what Japan has unleashed onto the world.

"The rockets came like drums, beating in the night."

From "The Martian Chronicles" by Ray Bradbury

Walter Gripp is the last man on Mars. All the rockets to Earth have launched without him. One evening in a deserted town, he hears a phone ringing. This creepy scenario from Ray Bradbury's The Martian Chronicles has captured the fascination of science fiction fans for decades. The reader wonders, who could it be? The scientist wonders, what would it sound like? We're about to find out...maybe.

Read More...

"Cooking is like music: you can tell when someone puts love into it.”

Taylor Hicks

The transition from mono to stereo music recordings in the late 1950s had its challenges. Find out how Rudy Van Gelder and other recording engineers worked out the details.

Read More...

"Every crowd has a silver lining.”

P.T. Barnum

126.4 I think that's what will be inside a little oval sticker that I'm going to put on my bumper. I see "26.2" bumper stickers that marathon runners proudly display. Colorado mountain climbers have "14er" stickers. A lot of dads are number "1." Then what's so special about 126.4? It used to be a number for Kings, but now it's a number for Cats.

Before I start to sound like a broken record, let me back up and tell this story from the beginning. Team Cornett wanted to raise the profile of UK Health Care and their close association with UK Athletics, so they came up with a plan to get the attention of a sports crowd. There's no better place for a hyped up crowd than Rupp Arena in downtown Lexington. With nearly 24,000 people, its been known to get really loud in there. It would be the perfect place to try and break the world record for the loudest crowd roar at an indoor sports event. And what basketball game would have the biggest and loudest crowd? A made-for-ESPN-TV marquee matchup: Kentucky versus Kansas.

"New Year’s Day… now is the accepted time to make your regular annual good resolutions. Next week you can begin paving hell with them as usual.”

Mark Twain

Have you made your resolutions yet? Why bother, no one keeps them anyway. So let's talk about resolution instead. In particular how low-resolution MP3s can affect your emotional reaction to music. In a study out of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST), researchers found that the fidelity of an MP3 recording of musical instruments can affect their emotional characteristics.

"The key to this plan is the giant laser. It was invented by the noted Cambridge physicist Dr. Parsons. Therefore, we shall call it the Alan Parsons Project."

Dr. Evil

Austin Powers

Here's something that will blow your mind and make you paranoid at the same time. Someone can listen to your conversations in your house or office from hundreds of feet away using light. The "light" is a "laser," and it's bounced off a window pane to detect sound vibrations. It's hard not to imagine Dr. Evil, played by Mike Meyers, air quoting "laser" when we mention that word. The theory was first proposed in the 1940s, but had to wait until lasers were actually invented in the 1960s to gain traction. By the 80s, the Cold War had us and the Soviets spying on each other using "lasers."

Read More...

I was afraid that science-fiction buffs and everybody would say things like, 'You know, there's no sound in outer space.'

George Lucas

The universe, according to scientists, started with a big bang. Let me, the sound engineer, just gloat a little bit here -– they don't call it The Big Flash, The Big Light, or The Big Visual Thing That Was Really, Really Quiet. It was a BANG!!! It all started with sound. And the cool thing is, we can even measure its echoes.

“Square in your ship's path are Sirens, crying beauty to bewitch men coasting by;

woe to the innocent who hears that sound!”

by Homer in The Odyssey

I live on a busy street. My house sits roughly between three hospitals - all with helipads and emergency rooms. That's good for me if I have a really bad day, but my poor cat thinks wolves are after her whenever someone else is having a really bad day. I'm talking about the incessant sirens going up and down my street. And they seem to be getting louder – they penetrate my windows and brick walls with even more ferocity than ever before. It turns out that I'm not imagining this, because some emergency vehicles are now employing something called "low frequency system," or LFS. I call it "Loud F*@#$%^& Siren."

In addition to the regular high yelp of a siren, you may have noticed a lower yelping sound that seems to penetrate your car and go straight through your chest. That emergency vehicle has a secondary siren system that emits powerful omnidirectional bass tones from about 200-400 Hz. In this range, sound is "felt" more than heard - up to 200 feet away. These frequencies can penetrate auto glass and metal, wood and brick buildings, and human flesh and bones.

The sellers of these types of sirens call them "intersection clearing" devices. They didn't make them just for fun, there is a real need for something to gets more attention. We live in a world of super-quiet cars, people with earbuds playing music loudly, pedestrians hunched over their phones while walking into fountains, and general inattentiveness. City dwellers in particular have learned to tune out the pervasive sirens that scream past them daily. There have been countless accidents, some fatal, at intersections while an emergency vehicle is on a Code 3 run. Police and fire departments are continually searching for solutions that make emergency runs efficient and safe for everybody, but it's an uphill climb.

This latest solution of using enhanced low frequency sounds is not without its controversy. Opponents complain of ever increasing noise pollution. They also bring up the lack of legislation regarding the use of LFS. For instance, many police and fire departments that are purchasing the LFS units are small towns without the traffic problems of big cities. People who live or work in cities that employ LFS sirens are subjected to particularly invasive sounds while inside a building, even on the 20th floor.

And these loud and low tones aren't just an annoyance, they can be harmful to your health. Noiseoff.org says "The intense sound caused by the [LFS] siren easily triggers an involuntary stress response commonly known as 'fight or flight.' This results in the secretion of adrenaline, with ensuing spikes in cardio-respiratory rates, muscle tension, and elevated blood pressure."

But let's not forget about the police officer or ambulance driver who is sitting on top of this thundering klaxon. At ten feet away, roughly the length of a pick-up truck, these sirens emit a powerful 123 dB-SPL. Let me put that in context for you. If you were standing at the goal line of a football field and a jetliner took off 65 yards away, you probably wouldn't notice that the jet was slightly louder than the siren because you would be screaming in agony from the pain. Makers of these LFS sirens don't recommend users subject themselves to more than ten seconds of the bone rattling sound, so they usually build in a failsafe cut-off time of the tone. But once it ends, nothing stops the operator from sounding it again and again.

Clearly, there needs to be more engagement between the public agencies and the public they're supposed to protect. An effort to educate both the protectors and the protected will only help everybody in the long run. These LFS sirens are getting the attention of people in the way, but at what cost? Will their overuse cause heart attacks, panic attacks, or deafness? If people then start to ignore these, will the police come up with something even louder? Like something that goes to 11?

"Someone needs to buy a radio station, then play nothing but audio books, with a different genre of book played at set times. That way we can always have something new to read, no matter where we are."

Shana Chartier

We're wrapping up our series on the audiobook this month. In Part 1, we began our conversation with veteran actor and audiobook narrator Brad Wills. He talked technical details about finding the right studio, performance, editing, and quality. In Part 2, Brad shared his methods of character development and preparation, plus he had some tips for budding narrators. In this issue, we're looking at how an audiobook is actually produced, from recording and editing, to mastering and delivery.

Read More...

“When you read a book, the story definitely happens inside your head. When you listen, it seems to happen in a little cloud all around it, like a fuzzy knit cap pulled down over your eyes.”

Robin Sloan, Mr. Penumbra's 24-Hour Bookstore

We're continuing our series on the audiobook, an older idea that has been reborn from new technology. In this issue we're talking with Brad about character development, preparation, and tips for budding narrators.

“I love audio books, and when I paint I’m always listening to a book. I find that my imagination really takes flight in the painting process when I’m listening to audio books.”

Thomas Kinkade

We begin a three-part series of how an audiobook is produced. We talk with veteran actor Brad Wills, as well as dive deep into how an audiobook is produced from the ground up.

"I used to judge the quality of music by whether I could make a 90-minute cassette and not repeat any artists."

John Hughes

What? Another old audio format is making a comeback? Yessiree! If you want to be hip, then dust off your old Sony Walkman. But like me, you've probably dumped all your old cassettes along with your floppy disks and Trivial Pursuit. These days, my pocket can carry the same amount of music that drawers and drawers of cassettes can.

Read More...

"I hate modern car radios. In my car, I don't even have a push-button radio. It's just got a dial and two knobs. Just AM."

Chris Isaak

Maybe you haven't noticed, but AM radio has pretty much sucked the last twenty years or so. Maybe you didn't notice because you weren't listening. A lot of people aren't, and the FCC is out to change that. The FCC? You bet – this isn't your father's FCC. We're so used to hearing "FCC" and "restrictions" in the same breath, that broadcasters were pleasantly surprised last October when the FCC announced an "AM Revitalization" initiative.

"I throw more power into my voice, and now the flame is extinguished"

Physicist John Tyndall, 1857

There's been a recent breakthrough in fighting fires - using sound waves to extinguish flames. Since 1857, scientists have known that sound waves could put out a flame, but they weren't exactly sure why.

Read More...

"As so much music is listened to via MP3 download, many will never experience the joy of analog playback, and for them, I feel sorry. They are missing out."

Henry Rollins

There's a growing trend in the music business - recording to reel-to-reel tape. Wait, I thought we got rid of that when we went digital. The truth is, it never went away. Much like the recent boom in sales of records and film, reel-to-reels are gaining new fans and bringing back old ones.

"I hope I inspire people who hear. Hearing people have the ability to remove barriers that prevent deaf people from achieving their dreams."

Marlee Matlin

Did you know that more than 37 million Americans aged 18 or older have some kind of hearing loss? And 30 million Americans aged 12 or older have hearing loss in both ears? With a media-rich society, that makes listening to narration, dialog, and speech in general difficult for them. Before 1972, anyone hard of hearing had to watch television with the volume turned up.

"If it weren't for Philo T. Farnsworth, inventor of television, we'd still be eating frozen radio dinners."

Johnny Carson

Eighty-six years ago, three musical tones, "G-E-C," were played on a fledgling network of radio stations. What started as a technical cue for local stations, has become an instantly recognized trio of notes woven into the American identity.

Read More...

"They number girl spies different. She's what you call a 36-23-36."

Max Baer, Jr. as "Jethro Bodine"

"Podcasting - I swear to you - on its worst day, the podcasts are better than our best films. Because they're more imaginative, and there's no artifice, and it's far more real."

Kevin Smith

Modern podcasting has now been around since about 2005. The roots go back much further, into the 1980's in fact. The idea of subscribing to an internet-delivered audio service dates to the early 1990's. But it wasn't until portable devices, such as the iPod, came onto the scene that it really took off. History shows that portability drives popularity – the battery-operated radio, the portable record player, the audio cassette, and the funky 8-track. I remember the iPod being described as a digital "Walkman," even though poor Sony already had moved beyond the cassette into portable digital players.

"Science is magic that works"

Kurt Vonnegut

"If a tree falls in the forest, and hits a mime, does anyone care?"

Gary Larson

"In radio, they say, nothing happens until the announcer says it happens."

Ernie Harwell

Legendary Detroit Tigers Announcer

There was a time when Americans who wanted to sound important and upper class spoke with a half-American, half-British accent. They call it mid-Atlantic, presumably because the accent lands somewhere in the middle of the ocean between our countries. It was dominant in movies, on radio, in theaters, and on early television. Today, it sounds pompous. Some early practitioners were Franklin Roosevelt, James Cagney, Orson Wells, and Katherine Hepburn. Some more contemporary holdouts were William F. Buckley, George Plimpton, and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

"Words mean more than what is set down on paper. It takes the human voice to infuse them with deeper meaning."

Maya Angelou

"What the eyes see and the ears hear, the mind believes."

Harry Houdini

"It is a cliché that most clichés are true, but then like most clichés, that cliché is untrue."

Stephen Fry

"Before anything else, preparation is the key to success."

Alexander Graham Bell

"Any effects created before 1975 were done with either tape or echo chambers or some kind of acoustic treatment. No magic black boxes!"

Alan Parsons

"People don't appreciate music any more. They don't adore it. They don't buy vinyl and just love it. They love their laptops like their best friend, but they don't love a record for its sound quality and its artwork."

Laura Marling, musician

We love convenience. Drive thrus, same-day delivery, automatic transmissions, instant coffee. Uh, maybe not that last one. Convenience often drives technology. And when it does, something has to go. What are you willing to give up for convenience? Taste, comfort, money, quality?

“There is a time for many words, and there is also a time for sleep.”

Homer, The Odyssey

If you've read The Odyssey or The Iliad, then you know why they've been literary classics for almost 3,000 years. But did you know they date to the earliest origins of the alphabet? It's believed that Homer's poems and speeches were so revered that early scribes dedicated themselves to writing them down. In fact, half of all Greek papyrus discoveries contain Homer's works. Homer must have been one cool dude to influence all of Western literature.

"I don't appreciate avant-garde, electronic music. It makes me feel quite ill."

Ravi Shankar

When you think of electronic music, you often think of the straightforward synthesizer, electric piano, or loops and samples. But some musicians like to rewire, alter, or downright reconstruct electronic equipment to make sounds they weren’t originally intended to do. At the forefront of these experimentations was BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop, a special music lab that gave us unique sounds and music for hit TV shows such as Dr. Who.

“Education is the kindling of a flame, not the filling of a vessel.”

Socrates

What young person really knows what they want to be when they grow up? Very few of my childhood friends are still on the path they laid out early in life. Most of us have zig-zagged through careers, including me. Unlike today, if you wanted to be an audio engineer in the 70's like I did, there were very limited educational opportunities. Most recording engineers started as musicians or disc jockeys and fell into the job. As a teenager in the late 70's, I was into music more than anything. I hung out in radio and TV stations and got my first exposure to a "real" recording studio in a friend's basement. I was a child of tape. In fact, as a child I ran around my house with a cassette recorder taping anything that I found interesting. I would often shove a microphone into the face of a shy family member, who would naturally be at a loss for words. But when a teen nears graduation, the pressure builds into making that big life decision - "what will I grow up and be?"

“Even if you're on the right track, you'll get run over if you just sit there.”

Will Rogers

It's said that when an early motion picture was first shown to the public, women fainted and men ducked from an approaching train. The director made a bold new decision that would alter the course of filmmaking for the next century. Instead of just placing the camera in front of all the action like an audience watching a stage, the director moved the camera to a new position - within the action - to create perspective. There were more changes on the way. About a hundred years ago, the first color and 3D films were being created. In an Avant Garde era when artists were distorting reality, most filmmakers were trying to recreate reality and immerse the viewers into it.

Read More...

The new generation is discovering what the old generation stopped loving - LPs. LP sales are the highs they’ve been in 22 years. Records aren’t just for hipsters anymore, everyone, including the older generation that gave them up, are groovin’ to them.

Read More...

“Within You Without You,” The Beatles

1967

How would you describe a sound to someone without using descriptors that are unique to sound, like: loud, bassy, shrill, whining, atonal, or noisy?

Not a problem, because we most often describe a sonic experience with words related to our other senses: sharp, warm, angular, raspy, piercing, even, warbling, soft, smooth, or flat.

Buzz Aldrin subliminally making the flag fly straight.

"Fly straight, you beep flag."

When astronauts first walked on the moon, everyone was glued to the television. I was eight-years-old and can remember it like yesterday.

Beep. Beep.

We copy you down, Eagle.

Beep. Beep.

Engine arm is off. (Pause) Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.

Beep. Beep.

What the beep? All those old NASA transmissions seem to have that beeping in the recording. What the beep is it? It's actually two, and they're called Quindar tones.

There was a recent AES (Audio Engineering Society) presentation at McGill University in West Montreal, Quebec titled "We Are the Robots: Developing the Automatic Sound Engineer." Brecht De Man from the Centre for Digital Music, Queen Mary University of London discussed the state of automatic mixing. I don't know whether to be happy some automation is on the way, or be alarmed that I may become obsolete.

I was recently explaining to our intern about how we used to synchronize sound and film together when I realized how many industry terms are borrowed from other tasks or re-hashed from another era. Most make sense, like "copy," "paste," and "edit." But with others you have to make an association.

The quest to create a 3D visual experience has revved up, sputtered, and stalled for almost a century. But the journey for a 3D experience in sound has steadily evolved for more than eight decades. The early 1930's saw the first experimentation with stereo, and the first feature film to be released in stereo was Disney's Fantasia, in 1940. Ray Dolby introduced the revolutionary and practical Dolby Surround to movie theaters in the 1970's (4 channels: left-center-right-back). The movie-goer was now immersed in sound from several directions. But when they went home, they were limited to a cheap monaural $3 speaker in their television set.

In the 1980's, television stations began broadcasting in stereo, and by the 90's in surround (still only 4-channels). For the average consumer however, having surround sound in the home was costly and reserved for audiophiles. But the new millennium brought maturity of speaker designs that allowed big sound from small boxes. Digital broke down the analog barriers to permit 6, 7, 8 and even 11 channels of surround sound.

Now more than ever, surround sound is accessible to everyone. A show of hands for everybody out there that has surround sound in their homes. I would bet that most of you didn't have it twenty years ago. It's so prevalent today, that it only makes sense to take advantage of it.

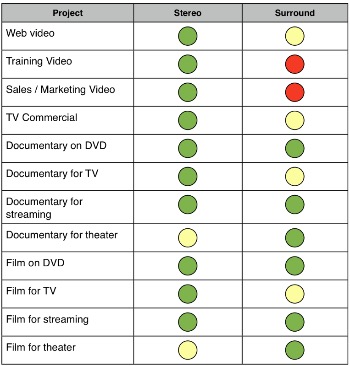

One of our services at Dynamix is surround sound. Our control room is set up to mix and deliver up to 5.1 surround. Should you do your next project in surround? It depends on the project and the listener's environment. The chart below offers a quick comparison of suggested final audio formats:

Some notes on the chart above:

Replacing dialog in video and film has come a long way since Clint Eastwood had to dub dialog for his spaghetti westerns. Whether it's noise in the original track, a changed or new line, or even a different performance, replacing dialog on programs and films is commonplace today.