- © 2003 - 2025 Dynamix Productions, Inc. Contact Us 0

"I got a chain letter by fax. It's very simple. You just fax a dollar bill to everybody on the list."

Steven Wright

William G.H. Finch had a crazy idea. He liked efficiency, and he liked news. He imagined a future that would merge those together for the average American. Americans like Joe and Jane. When they woke up in the morning, this crazy idea goes, a box in their parlor had just printed out the latest news onto paper with stories and pictures, ready to be poured over while eating their breakfast. Wait – that kinda sounds like the here and now. What's crazy is that this brainchild was born in 1933. William Finch saw a gap in the way Joe and Jane got their news. Newspapers, once the dominant source of news just a dozen years before, were relatively slow getting stories out compared to radio. Radio was instantaneous, but didn't have pictures like the newspapers. So he combined the two into a "radio facsimile" machine, or as they called it in the press, "radio printing."

Overnight, while Joe snored and Jane tossed and turned, radio stations transmitted data over their airwaves that sounded a lot like a fax machine does over a telephone line. A radio receiver was attached to a printer with a stylus that etched words, graphs, maps, comics, and pictures onto a roll of paper. These radiofax machines were small enough, light enough, and somewhat cheap enough to live in a family home. At least that was the plan.

The idea of printing electronic signals onto paper is not a new one. That endeavor goes all the way back to the 1840s with the telegraph etching a dot or dash onto paper. Crude pictures were being transmitted over wires in the 1890s. The first radio facsimile was patented in 1905 and was soon being used to transmit weather maps to ships at sea. By the early 1920s news services and amateur radio operators were transmitting pictures. In 1926 RCA was sending and receiving radio facsimiles between New York, London, San Fancisco, Berlin, and Buenos Aires by shortwave. Moving pictures, or television as we know it now, began to be developed in the 1920s as well. So maybe Finch's idea wasn't so crazy after all.

In the early 1930s, papers and radio stations were getting their news from such services as Transradio News Service that employed the teleprinter (similar to a teletype) and shortwave. Because phone lines were very expensive to lease during these days, news services were pushing the fairly new and rapidly advancing radio technology to the edge. Finch was part of this push while he worked for the International News Service. While he was building the first teletype service between New York, Chicago, and Havanna for INS, he was also experimenting with facsimile machines. He even invented a "talking newspaper" that printed a sound track on newsprint (like a movie's optical print) that played back as audio on a device in one's home. His patents would eventually number in the hundreds.

Finch quit the INS in 1935 and formed his own company, Finch Telecommunications Laboratories. He saw how large and complicated, not to mention costly, the facsimiles from big companies like RCA were. While they were commercially oriented, Finch was aiming at consumers. He focused on downsizing the technology while making it affordable and easy to operate.

The Finch radiofax

When Finch introduced his first model, it cost $125, about the same as a top-of-the-line iMac would today. Not an easy purchase for a family in the middle of a depression, but Finch was able to convince radio stations to buy the receivers in bulk for the earliest experiments in 1937. Finch hoped that positive press from the experiments and demonstrations like those during the 1938 NAB Conference would create demand.

RCA sure noticed and scrambled to produce a consumer version of their machines. They spearheaded the first regular transmissions of newspaper by radio by 1939 in St. Louis. RCA's receivers were double the size and price of Finch's but printed standard-sized newspaper font. General Electric and Western Electric also took notice and started development of their own versions. By the end of that year, nine stations in the U.S. would be regularly broadcasting radiofaxes. The new technology would receive even more attention at the 1939 World's Fair in New York.

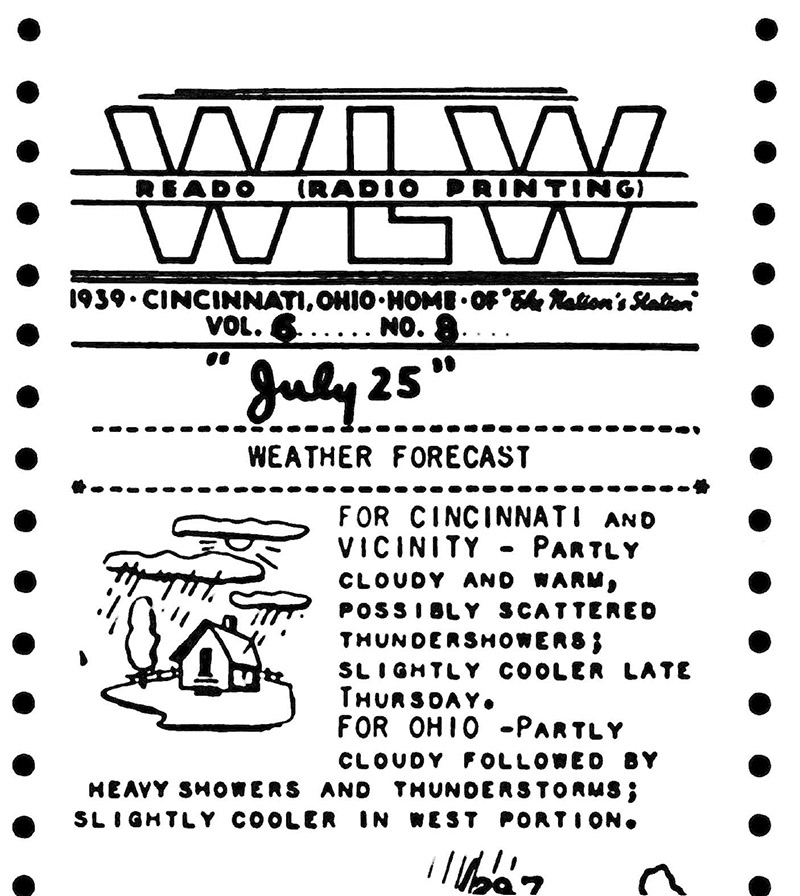

Then the king of affordable radio, appliances, and cars got in on the act. Powel Crosley, Jr. owned "The Nation's Station," WLW, and built radios to listen to his Cincinnati Reds on (if you weren't driving there in a Crosley automobile), so naturally he was interested in capitalizing on another crossover technology. Crosley licensed the technology from Finch and figured out how to make it even more affordable at $80 each. He called his radiofax the Reado. It was marketed as "Radio for the Eyes as well as the Ears."

A Reado printout

The momentum seemed to be building as more newspapers and radio stations began "radio printing" the news. A 1940 ad for the Crosley Reado, giddily predicts:

The art of transmitting pictures and other printed material by radio will advance. Nothing shall hamper its growth. Pictures of world events, cartoons, comic strips, news flashes weather maps, market reports, everything of a visual nature will soon be coming over the air. It is not anticipated that facsimile will directly compete with the newspapers. It will unquestionably be and continue to be a source of flash news rather than detailed mass printed material which can only be supplied by the newspapers and periodicals. Facsimile does not directly compete with sound broadcasting. On a separate channel, it will unquestionably be available as an augmenting service, providing a visual record of material other than music and sound being produced for your perusal whether you are present or absent.

But with all the hype, there were too many forces working against Finch, Crosley, and RCA. The first was that the Finch and RCA models were incompatible – exactly like the VHS/Betamax war several decades later. The AM radio signal had to be nearly perfect or else whole pages of content would not print, and those that did took too long. FM radio was gaining ground, and television was capturing the public's imagination. And last but not least, the country was still in a depression. By the end of 1940, only three facsimile stations were still transmitting. After World War Two, Finch and others tried reviving and improving the technology, even getting part of the new FM broadcast band reserved for facsimile transmissions for a short time. But television was on a fast track to America's hearts and wallets.

William Finch continued to develop facsimile technology after the war, envisioning news and information being delivered directly to consumers over standard telephone lines. He invented a color fax device. But none of these ideas took hold and his company went bankrupt in 1952. To add insult to injury, RCA took over many of its patents. William G.H. Finch died in 1990 at the ripe old age of 93, still working on inventions. His relentless push to improve and miniaturize facsimile technology led to what we now know as the FAX machine.

Today, radiofax is still alive. NOAA and other international weather services still supply weather charts via shortwave radio to sailors. Typically broadcast daily on four frequencies, a ship out of satellite or internet range can tune a portable shortwave radio to a given frequency, send the earphone output to a computer's audio input (or a purpose-built marine fax machine), and receive weather charts and other vital navigation information. It's amazing to think that a sailor's safety today can be credited to William Finch's crazy idea nearly 90 years ago.