- © 2003 - 2025 Dynamix Productions, Inc. Contact Us 0

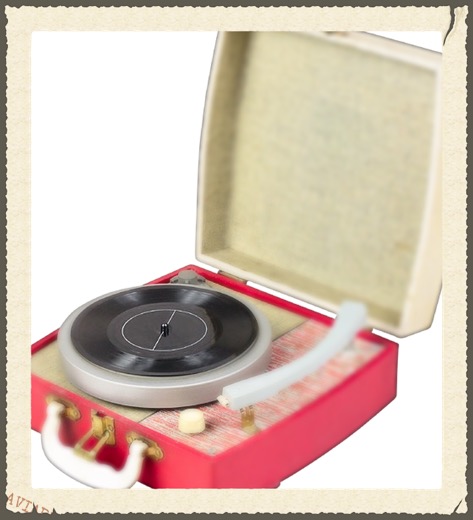

"People don't appreciate music any more. They don't adore it. They don't buy vinyl and just love it. They love their laptops like their best friend, but they don't love a record for its sound quality and its artwork."

Laura Marling, musician

We love convenience. Drive thrus, same-day delivery, automatic transmissions, instant coffee. Uh, maybe not that last one. Convenience often drives technology. And when it does, something has to go. What are you willing to give up for convenience? Taste, comfort, money, quality?

“There is a time for many words, and there is also a time for sleep.”

Homer, The Odyssey

If you've read The Odyssey or The Iliad, then you know why they've been literary classics for almost 3,000 years. But did you know they date to the earliest origins of the alphabet? It's believed that Homer's poems and speeches were so revered that early scribes dedicated themselves to writing them down. In fact, half of all Greek papyrus discoveries contain Homer's works. Homer must have been one cool dude to influence all of Western literature.

"I don't appreciate avant-garde, electronic music. It makes me feel quite ill."

Ravi Shankar

When you think of electronic music, you often think of the straightforward synthesizer, electric piano, or loops and samples. But some musicians like to rewire, alter, or downright reconstruct electronic equipment to make sounds they weren’t originally intended to do. At the forefront of these experimentations was BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop, a special music lab that gave us unique sounds and music for hit TV shows such as Dr. Who.

“Education is the kindling of a flame, not the filling of a vessel.”

Socrates

What young person really knows what they want to be when they grow up? Very few of my childhood friends are still on the path they laid out early in life. Most of us have zig-zagged through careers, including me. Unlike today, if you wanted to be an audio engineer in the 70's like I did, there were very limited educational opportunities. Most recording engineers started as musicians or disc jockeys and fell into the job. As a teenager in the late 70's, I was into music more than anything. I hung out in radio and TV stations and got my first exposure to a "real" recording studio in a friend's basement. I was a child of tape. In fact, as a child I ran around my house with a cassette recorder taping anything that I found interesting. I would often shove a microphone into the face of a shy family member, who would naturally be at a loss for words. But when a teen nears graduation, the pressure builds into making that big life decision - "what will I grow up and be?"

“Even if you're on the right track, you'll get run over if you just sit there.”

Will Rogers

It's said that when an early motion picture was first shown to the public, women fainted and men ducked from an approaching train. The director made a bold new decision that would alter the course of filmmaking for the next century. Instead of just placing the camera in front of all the action like an audience watching a stage, the director moved the camera to a new position - within the action - to create perspective. There were more changes on the way. About a hundred years ago, the first color and 3D films were being created. In an Avant Garde era when artists were distorting reality, most filmmakers were trying to recreate reality and immerse the viewers into it.

Read More...

The new generation is discovering what the old generation stopped loving - LPs. LP sales are the highs they’ve been in 22 years. Records aren’t just for hipsters anymore, everyone, including the older generation that gave them up, are groovin’ to them.

Read More...

“Within You Without You,” The Beatles

1967

How would you describe a sound to someone without using descriptors that are unique to sound, like: loud, bassy, shrill, whining, atonal, or noisy?

Not a problem, because we most often describe a sonic experience with words related to our other senses: sharp, warm, angular, raspy, piercing, even, warbling, soft, smooth, or flat.

Aaron Copland, 1970

WIth the recent news that the Library of Congress is inducting 25 entries into the Library of Congress National Recording Registry, I was excited to see U2, Linda Ronstadt, and Isaac Hayes get their due. Perusing the list, I saw a very influential (at least personally) album - Copland Conducts Copland: Appalachian Spring (1974).

I was a music major in college and always found Aaron Copland to be the quintessential American composer. He seemed to capture what Americans idolize about America: hope, boldness, charm, intrepidness, looking forward but not forgetting the past.

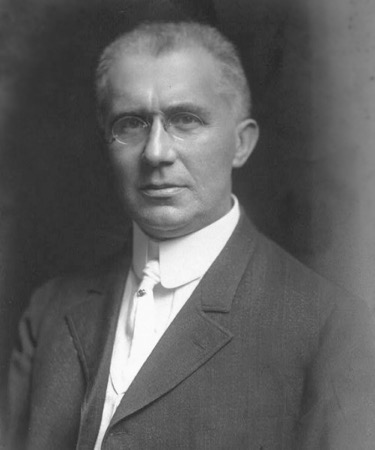

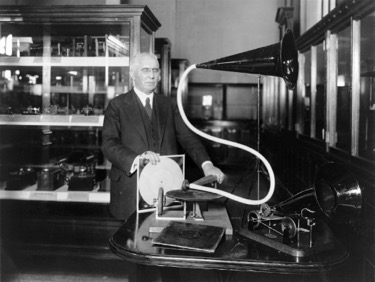

Emile Berliner

Analog rules!

When commercial radio really took off in the 1920's and 30's, it was fueled by advances in recording. You could even say that each drove the other. Early music recordings were mostly documents of what was already being played to live audiences - classical, early jazz, folk, etc. As bands got bigger and louder, the music got more exciting. Dixieland was new, records were all the rage, and radio was just beginning to transport the new sounds across the country, just like the transcontinental railway brought the ideas of the gilded age to America a half-century earlier.