- © 2003 - 2025 Dynamix Productions, Inc. Contact Us 0

PART I

The year '22 ushers in an exciting new technology. Here's what has been said about it:

"The newspaper that comes through your walls."

"Anyone with common sense can readily grasp the elementary principles and begin receiving at once."

"It will become as necessary as transportation. It will be communication personalized. There will be no limit to its use."

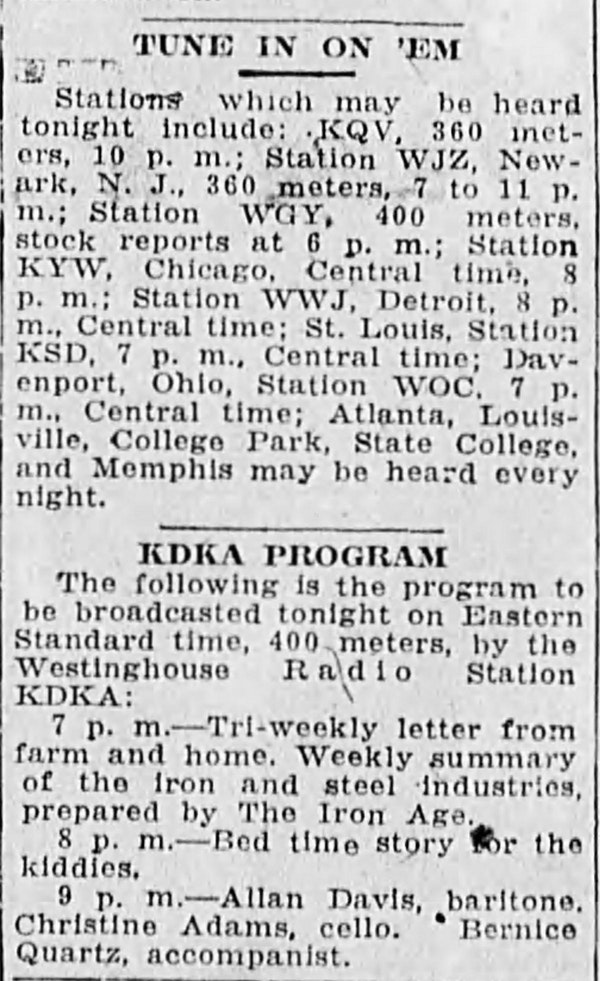

What is it? You might want to ask what year is it? It was the year 1922, and it's when radio for the masses exploded into homes across America. It had been building steam for a few years since the end of World War One. That’s when transmitting restrictions were lifted. In 1919, Westinghouse engineer Frank Conrad began spinning Victrola records of concerts from his home-based amateur station 8XK to a couple of hundred other radio enthusiasts. Then his listeners grew to several hundred, some even writing in requests. In 1920, he broadcasted one of the earliest live concerts: his son playing piano. Westinghouse relicensed the station as KDKA soon after, becoming the first station to broadcast live presidential election results. KDKA was an important early pioneer of live radio performances.

Radio popularity grew because the vacuum tube had recently been perfected and could reliably amplify a radio signal. As a result, transmitter equipment became smaller and more affordable for the average person to set up a "radio shack" in their house. Many amateur radio operators began transceiving with each other or putting on music shows like Frank did. Receivers were also coming down in price for some families ($200, or about $2,800 today), but a DIY crystal set with headphones could be built at home for less than $10 ($140 today). John R. McMahon talked about his own adventures of making a crystal radio. His story starts with his neighbor’s attempts:

He had bought about three dollars’ worth of raw material, which looked suitable either for an embroidery party or a horse-doctor's kit. These things had queer names, like galena, cat's whisker and tickler. I surmised that the cat's whisker tickled the galena and this made the radio laugh. An important part of the apparatus was a wire-wrapped cylinder of pasteboard, this having been an oatmeal box which the maker had abstracted from the kitchen when his wife wasn't looking, and in so doing had left a trail of oatmeal all the way into the living room.

The Country Gentleman, 1922

So popular was making your own radio equipment that retailers sold out of supplies. So, people resorted to outright theft:

Chicago, Ill.--From all parts of the United States telephone companies are complaining about the forays amateur radio operators are making on public telephones in order to secure equipment they think will be suitable for their outfits. The seclusion of a telephone booth affords a good opportunity for the radio nut to acquire a receiver. The thrifty and unprincipled parties are greatly disappointed with results of sets equipped with ordinary telephone receivers--they won't work on the wireless sets. Telephone men are hoping the daily newspapers will tip off their readers to this fact and cut down the losses of telephone equipment.

Telephone Engineer, 1922

Amateur wireless operators are blamed by the authorities for the disappearance of telephone receivers from public pay station booths in Paris and other French cities of late. So extensive have the raids on the telephones become that the government has sent out a "general alarm" circular warning station operators and merchants to be on the alert.

Disappearance of the receivers, which can be used in radiophony, began shortly after the Eiffel Tower wireless station started broadcasting concerts and news.

Telephony, 1922

The rapid expansion across the U.S. of both stations and radio sets was phenomenal. Then Secretary of Commerce Herbert C. Hoover said:

We have witnessed in the last four or five months one of the most astounding things that has come under my observation of American life. This Department estimates that to-day more than 600,000 (one estimate being 1,000,000) persons possess wireless telephone receiving sets, whereas there were less than fifty thousand such sets a year ago.

This growth of licensed commercial broadcasting stations in 1922 was enthusiastically chronicled by Radio News Magazine:

June 1922. Ninety-eight radio stations were broadcasting music, concerts, lectures, and market and weather reports, according to the Department of Commerce on March 23. Among the sending stations are 10 newspapers, a church, a Y. M. C. A., several large department stores, and two municipalities. Many manufacturers, radio sales and equipment shops, and five universities are also sending out amusement features in several forms so that today "all who listen may hear," just as all who "ran" have been able to "read" for many years. Even Hollywood, Calif., has a broadcast.

June 1922. Today there are broadcasting radio telephone stations in 26 states of the Union.

August 1922. The growth of this class of radio stations has been remarkable; it jumped from 67 stations a little over two months ago to 274 today. Applications are filed on an average of about three or four a day.

September 1922. The states of Kentucky and Mississippi went on the Department of Commerce's Broadcasting Map last week when stations in Louisville [WHAS] and Corinth [WHAU] were licensed.

September 1922. On June 30th the Department of Commerce licensed the 382d broadcasting station, issuing 21 during the past week...The future of radio telephonic broadcasting seems assured, as the remarkable growth still goes on at the rate of about three new stations each day.

October 1922. When KDKA, the first broadcasting call, was assigned nine months ago to the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co., East Pittsburgh, Pa., even the Chief Radio Inspector did not suspect that today there would be 451 stations broadcasting, one or more in every state except Wyoming.

December 1922. Broadcasting still continues in all but one state in spite of the pessimistic reports from some quarters that this service, which is likened to a fad, is falling off and likely to collapse.

December 1922. Broadcasting with the issuance of a license in Laramie, Wyoming, [KFBU] every state in the Union has one or more broadcasting stations.

Ma Bell (AT&T) was determined not to be left out of the sudden popularity of radio. It had already been developing radio techniques for extending telephone call service for several years, so AT&T easily stepped into the commercial radio business. Its first station, WEAF (now WFAN) in New York, went on the air in February 1922. AT&T's goal from the start was to build a radio network. Less than a year later, WEAF and WNAC (now WRKO) in Boston were linked together for radio's first network broadcast. Two more stations joined the network in the following months. What’s important to know is that this was done over telephone lines, which they controlled.

As new listeners tuned in to news, sports scores, impromptu musical performances, records, and even bedtime stories, business owners took notice. This was a prime opportunity to advertise to a very captive audience.

When radio with the start it already has, receives the further thought and scientific development of the next few months it will be completely adapted for many kinds of commercial enterprises that do not employ it as yet. It will become as necessary as transportation. It will be communication personalized. There will be no limit to its use.

How to Retail Radio, 1922

The radio boom had created a whole new market for industries, some selling directly to the radio enthusiast:

It is in the sale of batteries for radio work and in the recharging of them that the battery man can 'cash-in' on the radio phone 'craze.'

The Automobile Storage Battery, 1922

Selling radios and the batteries to make them work was one thing. Selling on the radio became a whole new industry. The first radio broadcast advertisement was on WEAF on August 22, 1922 at 5 PM. AT&T had built its telephone business on charging by the minute, so it was only natural to parlay that business model over to radio. Hawthorne Court Apartments in Jackson Heights, New York bought 10 minutes of airtime for $50. By October, WEAF had sold $550 in advertising. Executives called their simple formula of trading airtime for dollars "toll radio." It was here to stay.

For advertising to be successful, the programming had to be enticing to listeners. Everybody was learning this new craft and stumbling through each broadcast, but a few started to develop regular programming in 1922. The previous year, Frank Conrad advertised schedules of music entertainment to be played on his little amateur station in Pittsburg. His listeners ballooned from 200 to 400 almost overnight. Horne's Department Store advertised that his radio station could be heard on radio sets sold by Horne's:

AIR CONCERT "PICKED UP" BY RADIO HERE

Victrola music, played into the air over a wireless telephone, was "picked up" by listeners on the wireless receiving station which was recently installed here for patrons interested in wireless experiments. The concert was heard Thursday night about 10 o'clock, and continued 20 minutes. Two orchestra numbers, a soprano solo- which rang particularly high and clear through the air- and a juvenile "talking piece" constituted the program.

The music was from a Victrola pulled up close to the transmitter of a wireless telephone in the home of Frank Conrad, Penn and Peebles avenues, Wilkinsburg. Mr. Conrad is a wireless enthusiast and "puts on" the wireless concerts periodically for the entertainment of the many people in this district who have wireless sets.

Amateur Wireless Sets, made by the maker of the Set which is in operation in our store are on sale here $10.00 up.

Gwen Wagner, another radio pioneer who did just about every job at the upstart WPO in Memphis, Tennessee, shared that station’s program from its innaugural broadcast in 1922:

7 p. m.--Baseball results.

7:05 p. m.--News brevities.

7:20 p. m.--Cortese Bros. on harp and violin.

7:50 p. m.--Bedtime story.

8:10 p m.--Selections on the reproducing piano.

8:30 p. m.--New records on the phonograph.

Radio Age, September 1925

Music was often heard on this newfangled device – sometimes out of true desire by the operator to enrich the lives of listeners, and sometimes just to fill time. One thing was certain, live music sounded better than music from records. That's because radios used electrical microphones, and records were still being recorded and played back mechanically (you know, with the big bell protruding from the tone arm). Electrical microphones weren't being used yet to produce records (though telephones had been using them for decades), and they were still being played back with a steel needle that was amplified by a large bell. As a consequence, radio exploded, and record sales fell off. It wouldn't be until 1925 that records began to start selling in large numbers again. That's when RCA Victor started recording with the better electrical microphones. They also built an electrical reproducing turntable that didn't need to be wound up.

Since radio was so new, many were having trouble figuring out what the audience wanted to hear. George H. Fischer, Jr. of Pierce Electric Company in Tampa, Fla. complained that "too many stations have persisted in filling the air with 'jazz' and nothing else." He recommended more variety because he had heard too many Sunday School sessions, lectures, pick-up bands, and "long-winded orators with no time limit and uninteresting subjects."

The big corporations and government felt incumbent to control what the public heard on radio. Most felt that classical concerts would enhance the lives of listeners. Scholarly lectures, school lessons, and church services would round out acceptable programming. Said one writer in The Radio Dealer in 1922, “In the territory where broadcasting stations are found in great numbers the ‘canned music’ may have little appeal but in the territories at a distance beyond the daylight range of the big stations it is almost a necessity.” However, the small independent radio stations were mixing up their programming, if you can call it that, with anything that came to mind, including jazz. These were heady days for both the radio operators and the listeners alike. They were experiencing the wild west of radio. But not for long.

The U.S. government wanted to be rid of playing music records on the radio all together "out of public good." The record industry and musicians’ unions had called on U.S. Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover to stop the practice. Part of the reasoning was that those industries depended on record sales, and the public was effectively listening for free. Soon after Hoover issued his moratorium, ASCAP and commercial stations entered into contracts to allow them to play music on the air. This started the growth of corporate-owned stations and networks, and the decline of small stations that couldn't afford the hefty fees.

Where one tuned on the radio dial to listen to their favorite station was also up for debate in 1922. The government, in its usual "wisdom," allocated two places in the radio spectrum for stations in December 1921:

Licenses of this class are required for all transmitting radio stations used for broadcasting news, concerts, lectures, and such matter. A wavelength of 360 meters is authorized for such service, and a wavelength of 485 meters is authorized for broadcasting crop reports and weather services, provided the use of such wave lengths does not interfere with ship to shore or ship to ship service.

On paper, having a separate place for farm reports and weather made sense. Farmers in remote areas would hopefully have a clear signal at 485 meters (about 618 KHz on the AM dial). Having everything else on 360 meters (833 KHz) had listeners quickly tuning back and forth throughout the day. As stations became plentiful, most occupying 360 meters, overlap became a problem. Stations had to vary their power throughout the day and night to avoid this, often without success.

The equipment that radio stations used was nascent technology in the early 1920s. When WLW went on the air in 1922, a broadcast engineer later noted that just staying on one frequency was impossible with early broadcast transmitters. The signal would drift up to 10 meters in either direction of 360 meters (810-850 KHz). The government eventually acquiesced and spread stations out across the now familiar AM radio dial. The only survivor from these early days in radio is the NOAA Weather Radio network, which maintains more than 750 transmitters and covers nearly 90% of the 50 states.

Radio had great potential, anybody could see that – including the newspapers. They saw doom and gloom ahead because their newspapers were being read on the air – without financial reward – though the real decline of newspapers happened later in the decade. Some publishers saw dollar signs instead and invested in radio to sell more copies. By the end of 1922, about 10% of the 570 stations in the U.S. were owned or controlled by publishing companies.

Today, media cross-ownership is as prevalent as ever, especially with television, the internet, and streaming mediums. Radio isn't as relevant as it was in the 20th century, but it's still alive and kicking. Edison Research says that 87% of all in-car ad-supported listening is traditional radio. 45% of all radio listening occurs in cars, 32% at home and 23% at work. The most listened to time period is mid-day (M-F 10 AM - 3 PM) which is about 27% of all radio listening. I hope there is still a big audience for that most important broadcast of the day: Bedtime story for the kiddies.