- © 2003 - 2025 Dynamix Productions, Inc. Contact Us 0

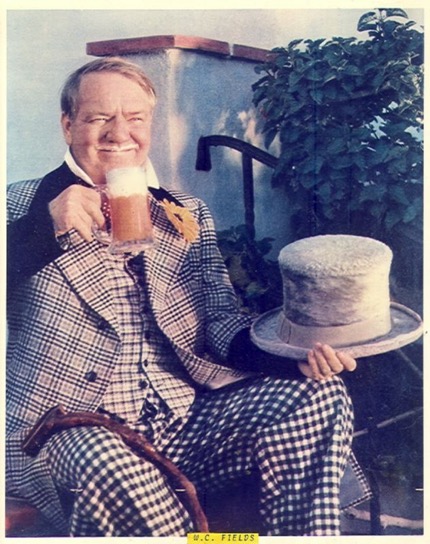

"Once, during Prohibition, I was forced to live for days on nothing but food and water."

W. C. Fields

January 2020 marks 100 years since the beginning of the "noble experiment" – Prohibition. The 18th Amendment banned the "manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors." Heralded in as a way to curb crime, especially domestic violence, it actually created a whole new cottage industry for organized crime and others to sell alcohol, sometimes with the help of law enforcement itself. When bars closed down, illegal nightclubs called "speakeasies" began to pop up. A club was often hidden from plain sight or disguised as another business, and a whispered password or secret knock got you in. When in public, patrons were asked to "speak easy" about its location.

The "Roaring Twenties" got its nickname from these speakeasies, the newly liberated women who were patrons, and the raucous jazz music that played in these illicit "gin joints." In most cities there were many more speakeasies during Prohibition than there were bars before the ban. To entertain these lively new crowds, owners often hired local African-American musicians to play a new up-tempo style of music. The crowds, a radically new mingling of men, women, blacks and whites, shared not only drink together, but a love for this new sound called "jass" – it was daring and exciting. Jazz wasn't really new, but few had heard it prior to the 1920s. Jazz had been played live in local clubs and traveling shows for the first few decades of the century. The first recordings of jazz weren't made until 1917. As those records spread to other cities and towns, musicians were listening and copying this radical new sound.

Simultaneous to the rise of speakeasies was the beginning of commercial radio, which also fueled the popularity of jazz. During the decade, those local jazz musicians began recording their music. These records were played on the nascent radio stations, and soon jazz was being heard by large numbers all across the country. Jazz was the first multi-racial music genre in America, and it was played by, listened to, and liked by both blacks and whites. Jazz music became the soundtrack of the Prohibition.

The earliest days of commercial radio were like the Wild West. Amateur and experimental stations, most of which transmitted with irregular schedules and changed radio frequencies throughout the day, grew in numbers after the World War. There were no assigned frequencies, and a license had to be issued to anyone that requested one. As technology improved, more got into the game. Department stores and manufacturers such as Powel Crosley, Jr. in Cincinnati bought transmitters and used the airwaves to sell their wares. Entertainment and news programs grew as the cost of owning a radio fell. Record sales fell as well, because the public was now hearing "free" music on the radio. The Radio Act of 1912, set up to license maritime and amateur stations, never foresaw the rapid growth of commercial radio. As more technologies like television and FM radio emerged during the decade, the government struggled with licensing and regulations.

The honor of the first station to be commercially licensed and broadcast in the U.S. is "up in the air." Most scholars recognize KDKA in Pittsburg as the most probable one to claim the prize. An amateur station started in 1916, it transmitted sporadically for several years under the call letters 8XK and 8YK. Their inaugural commercial broadcast as KDKA came on November 2, 1920, reporting the Harding-Cox presidential election results. Of all the earliest commercial stations, KDKA is the only one to retain its call letters and remain in its city of origin.

Speakeasies that either couldn't afford to hire a band or were limited in space used coin-operated phonograph players, known as jukeboxes today. The first models were acoustic players with big bells that channeled the vibrations from the needle. In a noisy nightclub, these were very hard to hear. When electric amplification came around in 1925, suddenly a record player could fill the room with jazz. In 1927, AMI released the first coin-operated electric machine that could play both sides of a record. These machines typically had a 20 song selection at 5-cents per play. Because record sales were hit hard by radio, so were coin-operated machine sales.

Another medium that propelled jazz into the consciousness of Americans was film. Talkies, or motion pictures with sound, started showing in cinemas in the late 1920s. (Read my article on the first optical film soundtracks here). Many of these early films during Prohibition featured famous jazz and swing groups that played in speakeasies, such as Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Ethel Waters, and Paul Whiteman. By the time Prohibition ended in 1933, jazz and swing had become mainstream. And thanks to a do-good movement by tee-totalers, we have a true American art form.